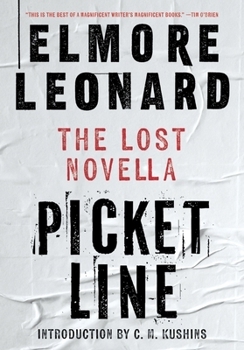

Elmore Leonard knew how people talk when something’s on the line. Cops, grifters, working stiffs, organizers—he caught their voices without dressing them up. That’s why the recent discovery of his short novella Picket Line feels like a small miracle for labor readers.

Elmore Leonard knew how people talk when something’s on the line. Cops, grifters, working stiffs, organizers—he caught their voices without dressing them up. That’s why the recent discovery of his short novella Picket Line feels like a small miracle for labor readers.

Picket Line captures what many of us have experienced as organizers or workers who have taken the extraordinary step of withholding our labor to make the boss come to terms with our demands.

Set in the late ’60s or early ’70s, Chino and Paco are Chicanos from LA driving through Texas farm country. They are wise asses (most of Leonard’s best characters are), but are they criminals? They stop to earn a little money, picking melons for a grower who has been struck by a farmworkers union.

Enter our organizers. Vincent Mora is a cerebral staff organizer of mysterious background, and Connie Chavez is a passionate, college-educated activist just learning the ropes of organizing. Skilled organizers can inspire workers to take risks they’ve never taken before, and Leonard captures exactly how Connie uses her megaphone to create hope, shame inaction, encourage defiance, and ridicule the boss—with humor and irreverence.

Around them are immigrant Mexican families in the fields, a couple of wild cards who don’t belong, racist cops, and a foreman enforcing the employer’s discipline. Leonard winds up the tension as workers leave the field to join the picket line.

A picket line is many things—exciting, boring, empowering, demoralizing. As Vincent Mora points out: “If a man comes out of the field and joins a picket line, he’ll never be the same again.”

Elmore Leonard captures that brilliantly, in a mere 100 pages.

Excerpted from Marcus Widenor’s review in the Northwest Labor Press.